A very common opinion regarding Full Length Battens is that they improve performance. Let’s look at that theory for a moment.

A mainsail with FLB has either has been refitted with Full Length Battens (FLB) or it is built from scratch as a new sail with FLB’s. There are a couple of things that happen in these two scenarios that lead to the “better performance” theory.

If an old main is retro-fit with FLB, one assumes there is a reason for it and it is usually to “improve the shape” often in conjunction with the owner’s desire to get another couple of seasons out of an old sail. We know that a sail’s shape degrades over time/use. Typically the original designed-in shape migrates to the aft part of the sail,or aft of where one would like it to be for optimum performance. The of course happens over time and so more or less creeps up on you. The observant owner will note that the shape IS migrating but more commonly he/she sees boats he used to be able to beat, sail past him, either racing or “not racing” if such a condition does in fact exist with two boats within sight of each other….. After the FLB retro fit, ideally done in such a way to “push” the shaping back towards where it needs to be, commonly the sail is now “faster” than before. After all that is what the owner spent a not small amount of money on.

Most sail boats are constrained either by the backstay or a rating rule or often both. This Sabre 38 main just overlaps the backstay at the top batten by about 4 inches. See the profile picture below

Thus there is a connection in the owners mind that FLB are faster than Non-FLB…

So the meme is that FLB are faster. Well kind of.

What happens if a new sail is ordered WITH full length battens? A few things:

Today there is a much greater likelihood that the roach on a mainsail designed within the past 10 years or so is going to larger than one from before that time. Sail making design uses lots of input from “racing” sails even when designing non-race sails and it is my experience that when an owner comes to replacing a sail for the same boat, and with Hood it might have been a fifteen or twenty year old sail, that the roach on the new sail is significantly greater than the old sail. More sail area never hurt any boat in the search for speed.

Second, simply having a new sail you are going to be faster than with an old sail-Just ask any one design sailor. Connected to this is the improvement in sail making materials, both Dacron and the rest of the fibers and manufacturing techniques for laminated sails.

Third, the above cited “improvements” in shaping ideas (and more powerful and detailed sail design software) can also come from a sail designer with a greater or different, skill, experience, attitude to designing a sail.

Another way to look at this question is to study for instance the J-105’s. They are a very competitive one design class with fleets all over the place. If one postulates that FLB ARE faster, then in theory all J-105’s would have full length battens. BUT even though the batten length is not restricted, or even mentioned in this class at least according to the class rules of 12 Feb 2012, section 6 to 6.4.1 Mainsails, if FLB WERE faster, then one would expect to see, in such a close racing fleet as the 105’s, all boats using FLB. But they are not. So what does this say about the performance of FPB? Are the FLB really “faster”?

Thus we now have a new sail with superior (compared to 10, 15, 20 years ago) shape holding properties. It is “bigger”, is almost certainly of a different design. AND it also has full length battens.

But which characteristic is making the sail faster? Is it the material, design(er), the extra roach, the newness of the sail and performance of the material or the battens?

Another detail to contemplate here is that the real advantage of FLB is the ability to support a bigger roach. This is doable in the majority of the boats on the market in the production arena but it is constrained by at least two things: Backstays and rating rules.

This Apogee 50 is used for cruising AND racing upgraded this older Hood Main which was about 12-13 years old and had seen lots ocean cruising miles. It was not designed with “girths” in mind. The new mainsail was made to the largest possible girths (for DH racing) and so is bigger than the old one pictured above..

Rating rules: as anyone who races even casually is aware one needs a handicap rating for their boat. One of the items in a rating is of course how big the sails are. A mainsail is measured not only by the P and the E but by at least one and up to as many as four so called “girths”. Briefly a girth is a dimension from a specified point on the luff, at a minimum 50% of the luff length across the width of the sail to the corresponding position on the leech that is 50% between the head and clew. Boats that are raced regularly are measured at 25%, 50%, 75% and sometimes 87.5% locations, reading up from the foot. At each measurement point the mainsail cannot be wider than a percentage of the foot. The current versions of these width percentages are:

MGT: The 7/8 point– 0.22% of E

MGU: next one down, ¾ points– 0.38% of E

MGM: Middle 50%–0.67% of E

MGL: the bottom ¼ points—0.89% of E.

Try this math on your own mainsail. There is a formula in the ORR rule for calculating the actual area including roach, if you have these measurements. Calculate the mainsail area: P x E x 0.5 which gives the basic triangle area. The inclusion of the girths gives the actual area. As a rule of thumb actual area is abut 20% more area than the basic triangle area.

The width of the mainsail on the majority of boats is constrained by either the backstay or a rating requirement. This Sabre 38 mainsail is built to the maximum girths permitted by the PHRF of New England. If you look carefully, the upper leech adjacent to the top batten, is just overlapping the backstay by about 4 inches.

Generally speaking these girth requirements constrain the width of the average mainsail to what we all commonly see on boats unless they are multi-hulls or open class offshore race boats, or high performance skiffs of the Sydney Harbor 18 footer type. That is a pretty basic triangle, like the one on the Sabre pictured above.

Backstays: The next item that constrains boats from having really big roaches is the backstay. Yes some boats come out of the box with provision for large roach mainsail and I am thinking of the Quest line of performance cruisers and race boats, designed by Rodger Martin and built by Holby Marine thru the 1990’s. They and others have girth restraints that allow for a wider main than those cited above, but the general rule for the vast majority of boats confirm to the cited percentages.

This cruising main has a very conservative roach, almost nothing. The owners commissioned a new sail and specified a much larger roach, so big in fact that when tacking they had to lower the mainsail a few feet. Notice the backstay is very close to the end of the boom which limits the roach/upper girths if you do not want the roach to hit the backstay.

The interesting thing is these “regular” girths, from the formulas above, keep the roach of the mainsail on most boats to just about where the backstay is plus or minus a few inches usually.

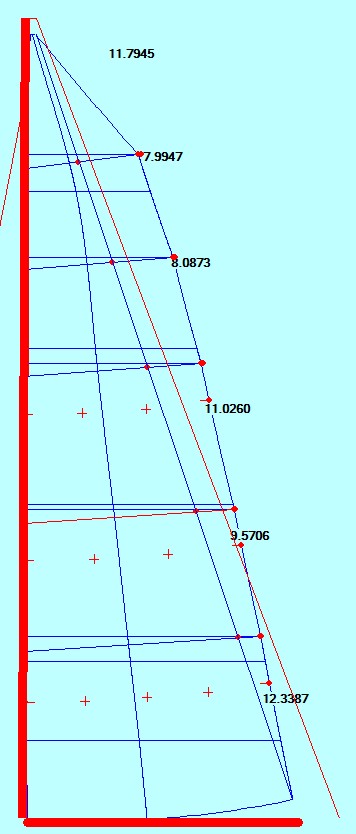

A (new) large roach mainsail for the cruising boat pictured above. The roach is so big the mainsail must be lowered to tack, this at the owners request. The backstay is indicated by the red line that terminates in the bottom right hand corner of the image.

Some cruising boats, most prominently the Deerfoot range of fast offshore cruising boats pioneered by the Dashews have much larger roaches BUT their rig layout, allows for this. The backstay is a long way aft of the end of the boom, so the roach can be big without fouling the backstay.

So bearing in mind all the foregoing, as to the question as to when FLB’s “might” be faster, one has to get outside the scope of “normal” racing rules, PHRF, IRC, ORR and so on and look at open class boats and other high performance boats-Aussie and Kiwi skiffs, most performance multi-hulls and so on. Here we find a mainsail, that has FLB but most commonly another feature not seen on the usual production cruiser racer or plain cruising boats-Square head mainsails.

The yellow line leading from the head, at the bottom of the image, to the clew at the top, is the straight line leech. All the sail to the image left of this line is roach. This of course requires considerable detail (read cost) in making sure the sail will be robust enough for hard offshore work typical of Deer foot owners. The blue line at the head is part of the tackle for the leech line which leads over the head of the sail so it can be adjusted at the tack.

The so called Square Head mainsail seen in the image at the top of this essay, takes advantage of the unrestricted nature of the sail area calculus of open class offshore boats and the various skiff classes’ by providing certainly more sail area, but also reducing drag at the top of the mast. This topic we will take up in Full Length Battens-3