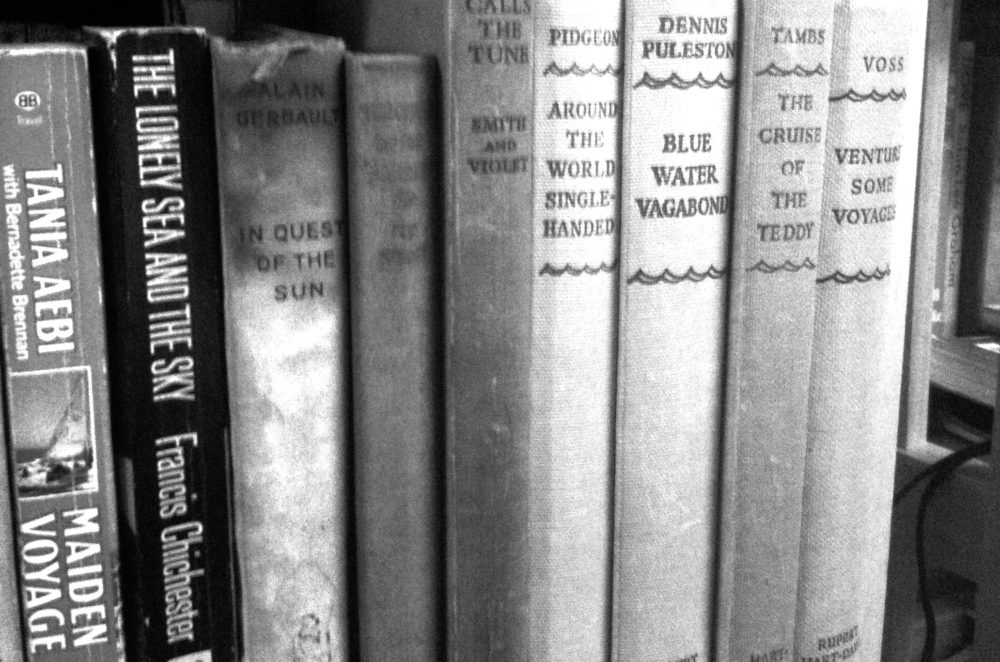

Regular readers will know of my interest in the Mini Transat, OSTAR, Vendee Globe, Figaro and similar solo and double-handed races. Apart from the actual racing itself, these boats represent a melting pot of ideas and were lots of smart people invent ways to sail fast when alone or with only two people. The majority of cruising sailors sail with a crew of only two people aboard anyhow. Short-handed boats prepared for racing have been at the forefront of most of the ‘advances’ that cruising sailors take for granted today. So when I see boats from this short-handed cohort of yacht racing, I am always curious to see what the thought process is and if there any new ideas I can pinch.

I was at Sail Newport last Sunday and I noticed the Mini Transat boat that, a couple of weeks ago was in the water, had been pulled out. I was interested in this boat because it had a canting keel, but there was no obvious dagger board or other device to resist leeway, at least as viewed from the dock with the boat in the water.

Not only canting side to side, but moving fore and aft close to a meter the fin on this Mini Transat class boat requires some pretty careful attention to detail. That she had a canting keel is evident by the lines exiting the cabin bulkhead under the cowling-see below-(and passing thru jambers) These lines are part of a three or four to one tackle inside the boat and then lead outside to a winch so as to lever the keel side to side.

The large clutch on the deck secures the line controlling the canting keel. The lines are set up to lead to a winch. The boat was set up with a canting keel but where the dagger boards?

This mini, designed by Simon Rogers for Australian Tom Braidwood and built in Sydney, Aust. in 2006 has both a canting keel , articulating from side to side and the keel moves fore and aft too.

574 looks, at first glance, like a ‘normal’ (And not like mine) mini: beamy, twin rudders, skinny fin with a big bulb, huge rig, and articulating bowsprit

Apart from the ‘canting keel but no dagger boards’ question, a second interesting detail was the mast. It is longer in section (fore and aft) than ‘normal’ mini masts and has only one set of spreaders. Hummm me-thinks.

MAST and Rigging

This boat has a mast with only one set of spreaders. It can do this because the mast is longer in the fore and aft plane and with probably thicker walls too. The underlying scheme here is to minimize windage, drag, from the rigging. The configuration of 574 is likely to have less exposed stays and certainly spreaders, than a ‘normal rig’.

Almost all of these speedy little boats, the custom ones, anyhow, have composite rigging today. Securing the shrouds to the boat is a wonderful throw back to the ‘old days when stays were lashed to the deck with lanyards and pad eyes.

The stays are secured to the deck/chainplates with Spectra line, with multiple passes around the chainplate and the stay. The black tube is what amounts to a reaching strut. This is inserted into a hole built for the purpose in the side of the hull. The end result is to hold the bow sprit after guy out away from the boat at a wider angle.

Underwater: The keel and canard

It turns out that this boat has a lot going on down below. The keel swings, or cants in the parlance, port to starboard. It also can move fore and aft 800mm according to the designers website.

Here you can see the root of the fin disappearing into its own mechanism to handle the canting. The longer orange rectangle is the pathway for the fin to slide fore and aft.

The fin on a canting keel boat enters into the hull through a suitable sized slot. There is an axel with bearings on it that passes through the fin along the fore & aft axis and is secured to the boat. Around the hole is a V shaped box, the top of which is above the LWL. This box has some kind of pretty waterproof cover on it too. The top of the keel pokes up thru this and has a block and tackle on the top. The line from this tackle is led outside thru a ferrule in the cabin wall as shown a few pictures above. I am not certain that the area around the keel entrance to the hull is race ready, but it seems to me there are a lot holes and slots that would create drag when sailing, especially, fast. ON the other hand this boat did correct to third in class in the Pacific Cup in

The object when designing a racing boat of course is to have a boat that can, and will, win races. All manner of calculus goes into the design engineering and building of such a boat. One of the curious aspects of this boat is the engineering and building detailing required to make the keel more fore and aft. This requires a lot of additional designing, engineering and boat building time and skill. All of this of course consumes (extra) money. In simple terms, what is the risk reward, or if you, like the cost benefit ratio.

The white ‘thing’ sticking down to the left is the canard, set forward of the keel. This is deployed to resist leeway, acting like a ‘normal’ keel on normal boats. That it can be canted too is a benefit because when the boat is heeling, the canard can be vertical and so be working most efficiently.

This boat is a close sister-ship to the one Jonathon McKee (a prominent and successful US sailor from the Pacific North-West) sailed in the Mini Transat in 2003. Sadly he was dismasted while leading the second leg of the race. I don’t know what style of mast McKee had, but the one on 574 is configured in a way that many of the new IMOCA 60’s are, which is interesting since this boat is 10 years old now. The idea is that the mast and standing rigging has a certain amount of drag.

And finally back to the mast

If you do the math on the surface area of the standing rigging on your boat—Sum the total length of standing rigging, multiplied by the various thicknesses, it is a lot of square units. Ignore for now the radar, radar reflector, satellite dome, spare halyards, the bulk of the furled headsail or staysail etc. Now, for the average 45 foot cruising boat, this kind of drag is repressed into oblivion by Bimini’s, dinghy davits and so on and traveling at 5 to 7 or 9 knots, BUT on a boat traveling at 15-20 knots, like a Mini or an IMOCA 60 traveling, as the boats currently leading the Vendee Globe are, at over 20 knots most of the time, for the foiling boats, drag becomes something to think about. Minimizing drag becomes especially important for boat traveling fast because the drag goes up exponentially with boat speed. Hence the wing masts and lots of effort art educing drag on fast Multihulls of IMOCA 60’s

This latest generation IMOCA 60 has the, now common, deck spreaders and wing section mast. The spreaders are there to get a wide shroud base, to minimize the compression on the spar so it can be a bit lighter. Many, many Excel spreadsheet Cells were sacrificed in figuring out the cost benefit of this arrangement.

The benefits of reducing drag are even more visible on big trimarans. This picture is courtesy of Spindrift Racing.