The latest from Spindrift 2 and IDEC as they rocket towards the Equator.

SPINDRIFT 2

Jules Verne Trophy record attempt Day 4

And remember, Spindrift 2 is THE boat that presently holds the 45 day record.

Position: 18 24.32’ N – 26 46.62’ W

274 miles ahead of the record holder, Banque Populaire V

Distance covered from the start: 2,254 miles

Distance traveled over 24 hours: 736.5 miles

Average speed over 24 hours: 30.7 knots

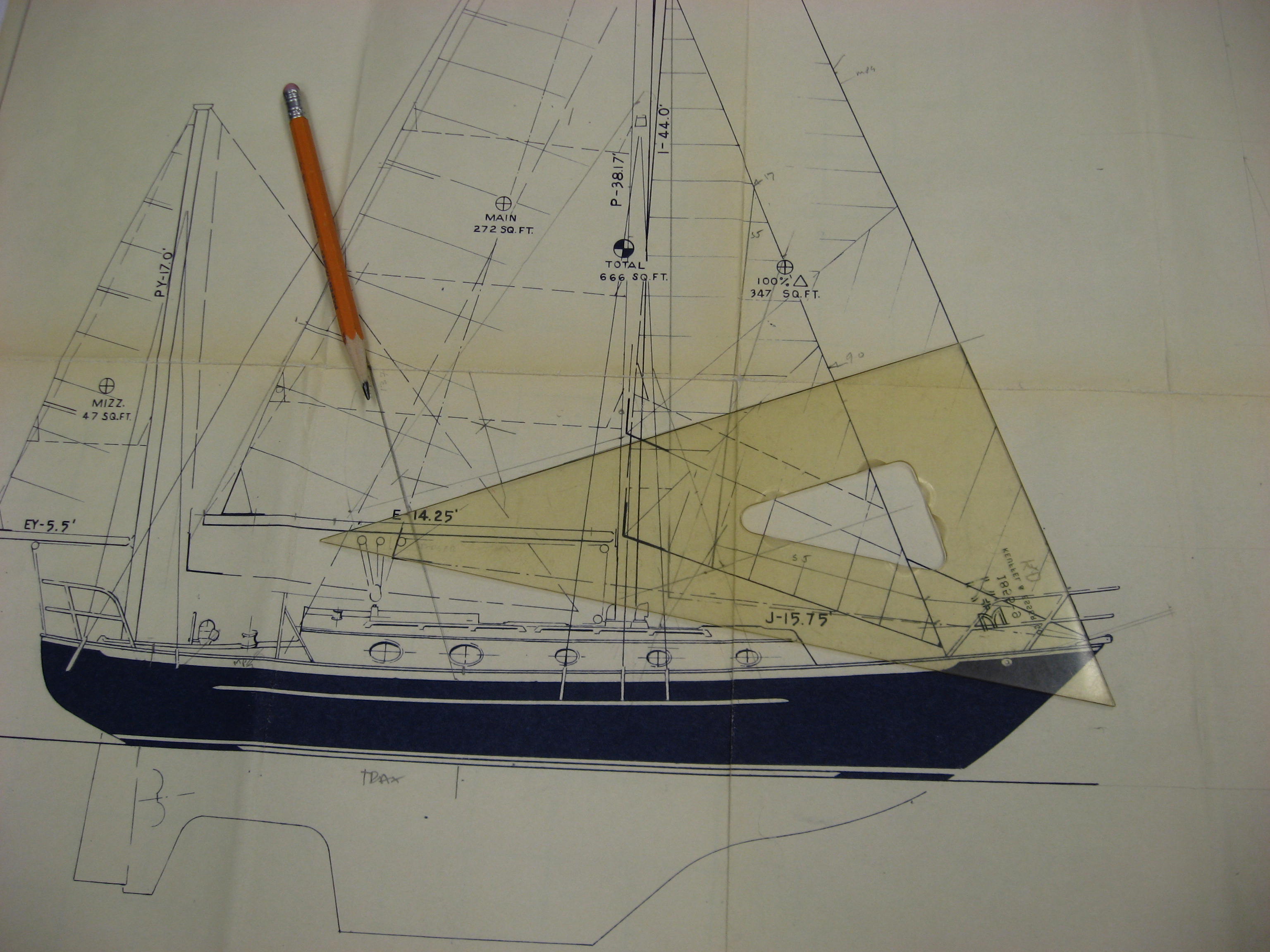

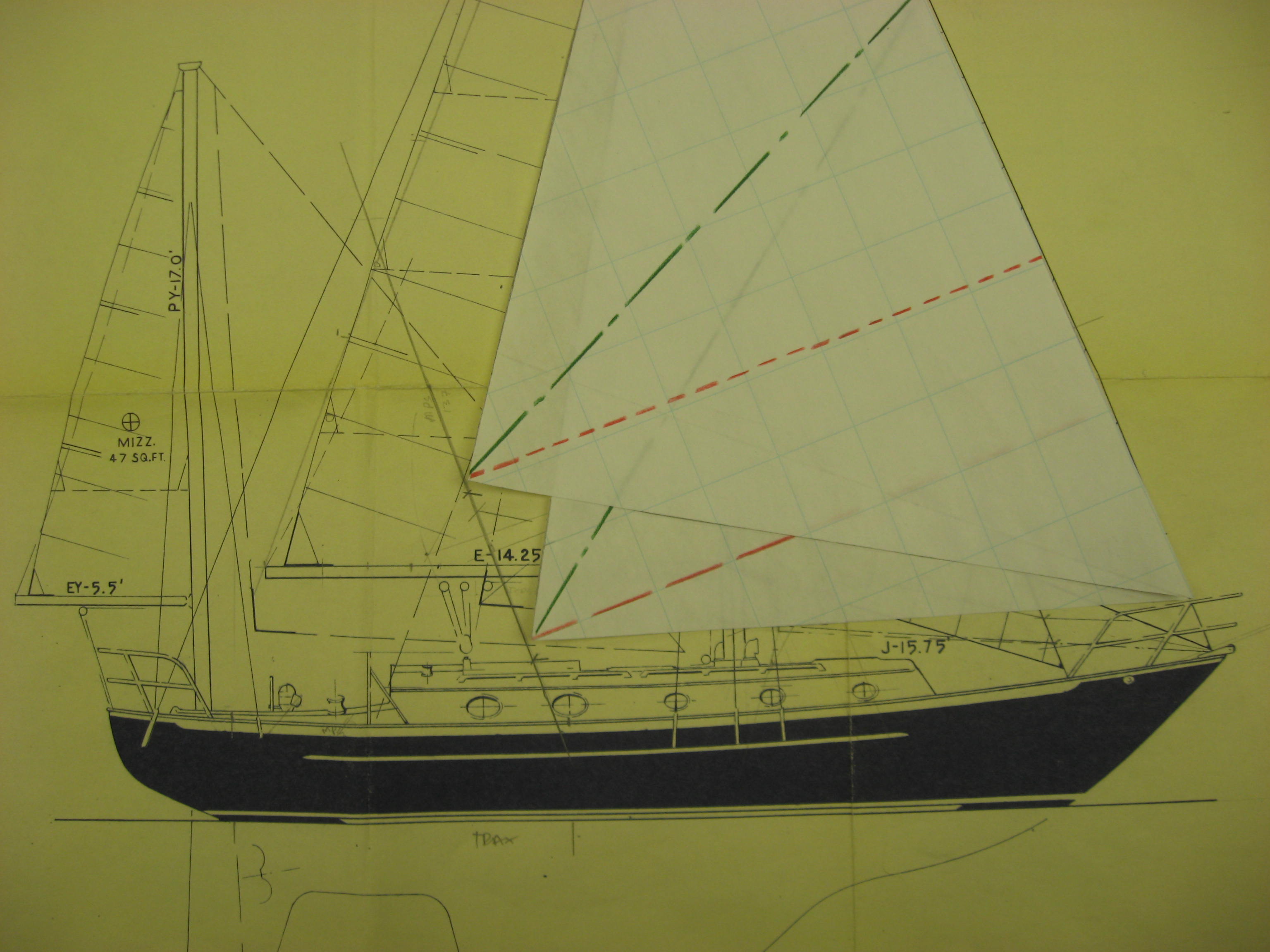

Sails: Two reefs in the mainsail, and the Solent

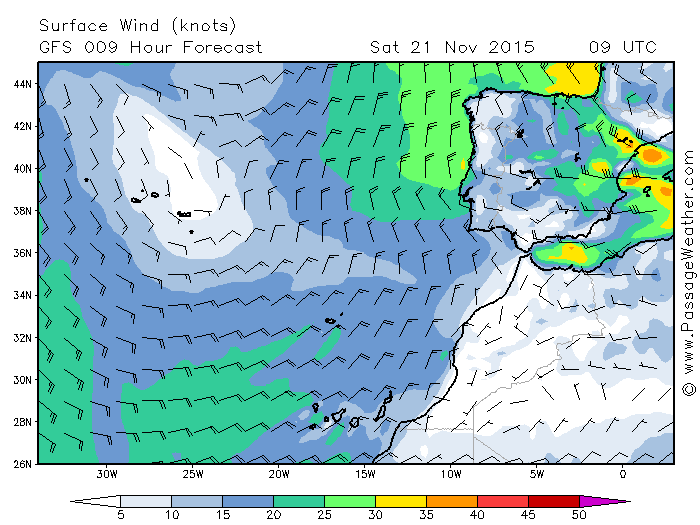

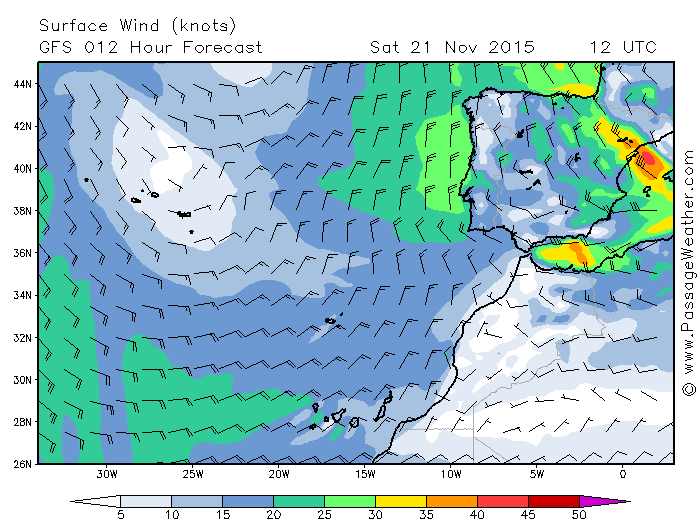

Area: Tradewinds of the Northern Hemisphere, Western Cape Verde, latitude of Dakar (Senegal)

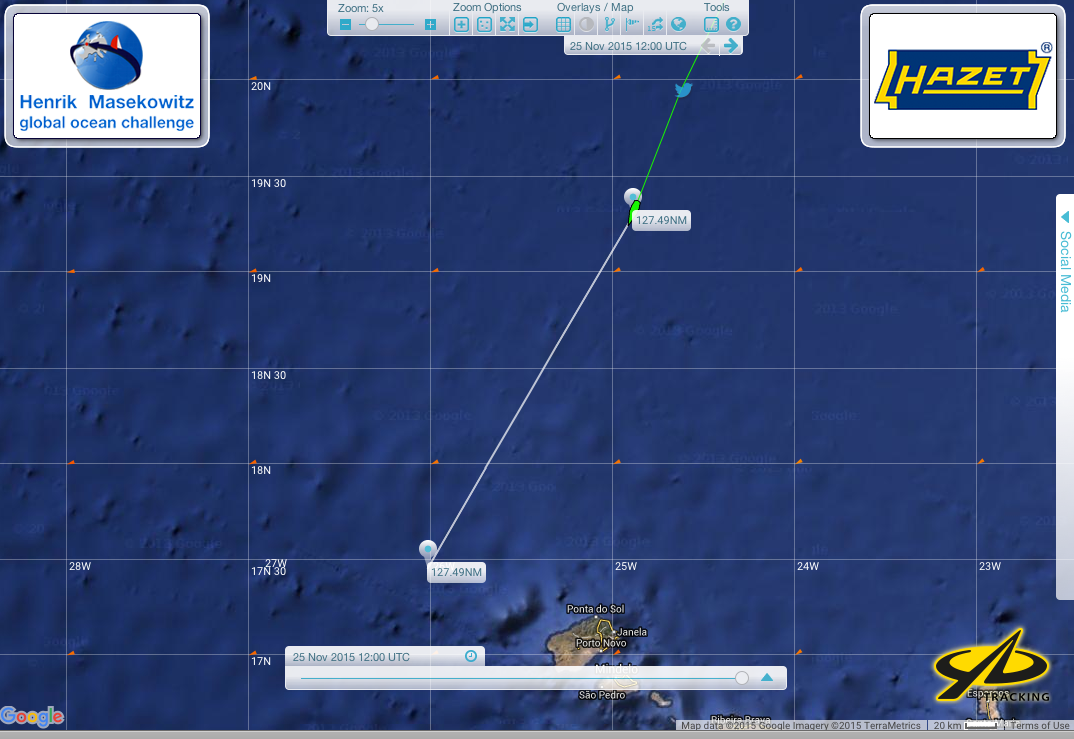

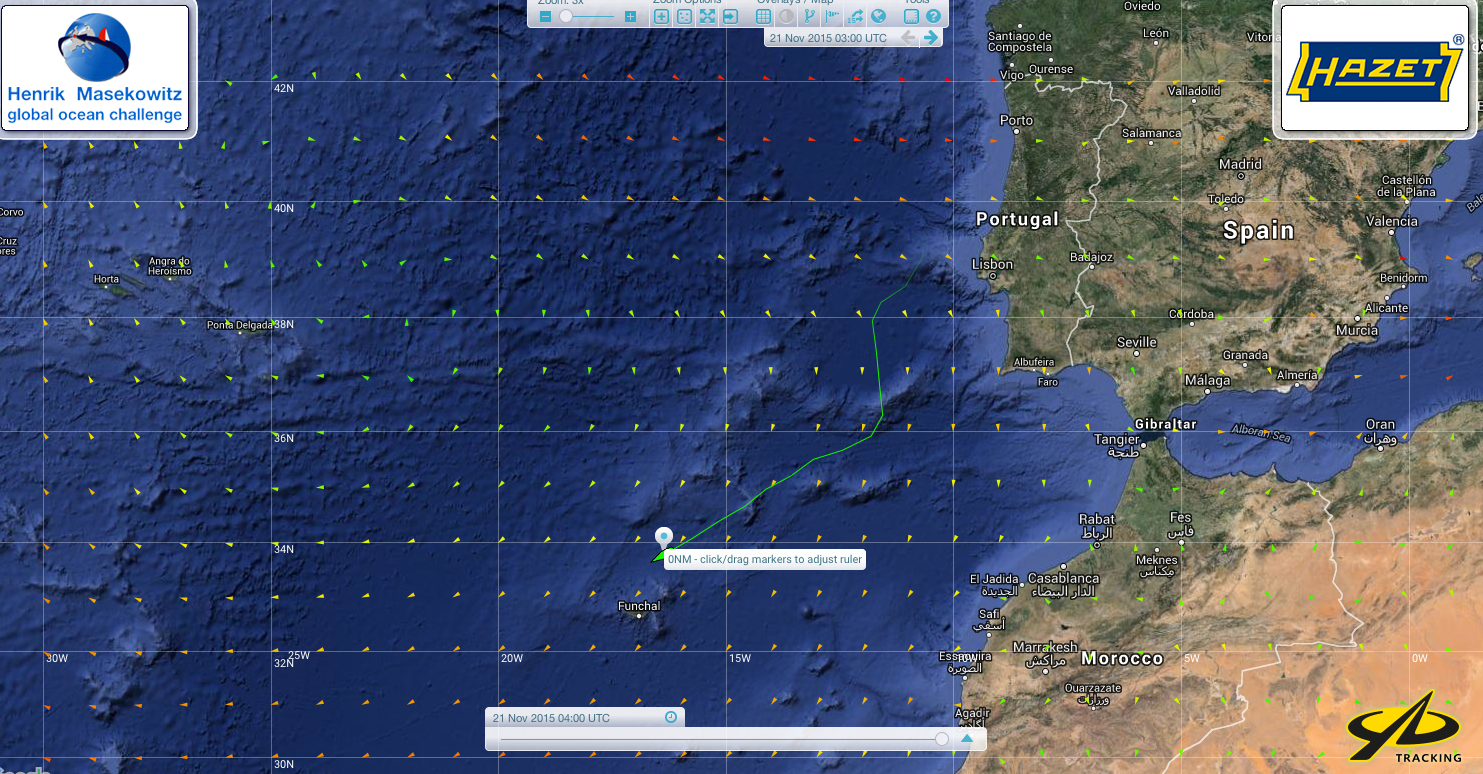

Roughly the relative locations of the two tris and Henrik. Seems as though he is safe now.Spindrift 2 is to the north, IDEC is to the south. Spindrift is over three hudred miles ahead of Banque Populaire, (that is her own pace,) for the same number of hours sailed.

Message from Dona Bertarelli:

Chatting over a coffee-grinder

“Isn’t it strange that we still haven’t seen any flying fish?” I ask Seb Audigane, who is at his post at the traveller, ready to ease off the sail immediately if the wind picks up. “It won’t be long,” he replies.

The water temperature indicator shows 22 degrees Celsius. Is it too hot or too cold for these small fish, whose wings allow them to leap out of the crest of the waves and fly several hundred metres on the water’s surface?

We’ve not seen many animals since we set off.

“We’ve not even seen any dolphins, yet we saw some at every training session on Spindrift 2,” I tell Seb.

“We’re going too fast for the dolphins,” he replies. “Only bluefin tuna can swim this fast.”

But unfortunately there aren’t many bluefin tuna, so they are a rare sight indeed. The bluefin tuna are currently listed as endangered species, so protecting them should be everyone’s responsibility. We should stop eating them to help stocks recover so that our grandchildren can see them, and perhaps also eat them.

At the current rate of consumption, there’ll be none left. Not even in aquariums, because these migratory fish travel hundreds of miles, crossing oceans at speeds of 80 km/h (50 mph).

The word tuna is derived from the Greek thuno, meaning to rush.

With torpedo-shaped streamlined bodies, Atlantic bluefin tuna are built for speed and endurance. They can even retract their fins to reduce drag, enabling them to swim through the water at incredibly high speeds. They are top ocean predators and voracious feeders, eating herring, mackerel, hake, squid and crustaceans. Unlike most fish they are warm-blooded and can regulate their temperature to keep core muscles warm during ocean crossings.

Their incredibly beautiful metallic blue topside and silver-white bottom help camouflage them from above and below, protecting them from killer whales and sharks, their main predators.

At 2-3 metres long, the Atlantic Bluefin is the largest species of tuna. One was reported to be 6 metres long! It’s incredible to think that they can dive deeper than 1 km.

When Bluefin is prepared as sushi it is one of the most valuable forms of seafood in the world. The species is listed as ‘near threatened’ on the IUCN red list. So let’s all think twice before buying some at our local markets. They might not be as cute as dolphins, but they are worth protecting!

– See more at: http://www.spindrift-racing.com/jules-verne/drupal/en/log-book/jour-4-journal-eng#sthash.PkMVrxcN.dpuf

AND FROM IDEC:

IDEC SPORT has kept up a very fast pace. Francis Joyon and his men are already off the Cape Verde Islands three days after setting sail from Ushant. The Equator is merely 1000 miles away and the record on this first stretch of the Jules Verne Trophy is set to be broken.

IN SUMMARY:

The record for the stretch from Ushant to the Equator

also held by Loïck Peyron and his crew on Banque Populaire V (Now Spindrift 2) since 27th November 2011 – is:

5 days, 14 hours, 55 minutes and 10 seconds.

At 0600hrs on Wednesday 25th November 2015,

IDEC SPORT was sailing at 32.9 knots at 17°32 North and 26°59 West, 90 miles West of the Cape Verde Islands. Bearing: south (201°). Lead over the record pace: 227 miles.

This long straight run will remain in the history books. The wind shadow of the Canaries is behind them and the steady NE’ly trade winds are blowing allowing IDEC SPORT to speed along at between 30 and 34 knots in the dark of night. This historic pace – two straight tacks down from Ushant – has given us some figures which are bound to please the six men on board. For example, they have now covered more than 2000 miles since leaving Ushant. You read that right. 2000 miles in just three days and three hours. To give you an idea of what that means, if that pace continues, they would complete the voyage around the world in around thirty days, but we know that getting the time down to less than 45 days is going to be tricky.

ALREADY 2000 miles in their wake

Logically at this very fast pace, the lead over the record time has increased. It was over 220 miles at 0500hrs this morning with IDEC SPORT approaching the Cape Verde Islands, which they will leave to port. Yesterday evening, the big red trimaran sailed by Francis Joyon, Bernard Stamm, Alex Pella, Clément Surtel, Boris Herrmann and Gwénolé Gahinet overtook the point Banque Populaire had reached at the end of her third day of sailing during her record run.

This morning, we can say that IDEC SPORT is 8 or 9 hours ahead of Banque Populaire. That is a lot after just three days of sailing. Remembering that at the moment IDEC SPORT is covering on average 715 miles a day and that there are just 1000 miles left to the Equator, it is likely that the record from Ushant to the line separating the two hemispheres (5 days, 15 hours) will be beaten and with a huge advance.

IDEC position versus Crois du Sud