The Candy Store Cup, staged out of the Newport Shipyard, in RI was held over 3 days, the last weekend of July. The Candy Store Cup is a dedicated regatta for Super Yachts, with the minimum LOA for entry of nominally 30 meters, around 100 feet. Such yachts are generally not the kind of boats high school sailors get the opportunity to sail on, outside of the owner’s family and friends. Fortunately I have a lot of mates in the area who know of my interest in, work with and passion for, having local high school sailors have the kinds of experiences I had as a teenager, well sort of. NOT too many 56 meter Perini Navi Ketches in Sydney town in the 1960s and 1970s.

A couple of weeks before the regatta I had an email from Murray Lord, principal at Wellington Yacht Partners and former yacht captain of small ships of this size. The note asked me if I was interested in sailing on Zenji for the Candy Sore Cup, and if so to contact the captain. Murray was to be the ‘race’ skipper.

One thing led to another and after meeting with Matt, the very pleasant and easy going British skipper, I got the nod. At the end of our discussions I raised one point of interest to me, ‘can I bring some HS sailors? After some more talking on this subject, Matt was gracious enough to let me bring up to three young sailors per day. Hot Dog, I thought.

I sent out the Bat Signal for another Cooper Kaper to the Prout School Sailing team email list on this topic. Short version? I was able to have 5 of the sailors, all young ladies, (80% of the 2017 team was ladies) rotate through the four days of sailing, one practice and three race days with me.

Well, ‘sailing’ on a 56 meter Perini is a rather different bag o’ sail ties than almost any other sailing. There is barely anything one person alone can do on deck, the kite sheets are probably 350 feet of 25 mm spectra, the dock lines not as long but twice as thick and even the fenders, light though they are being inflatable, are more easily managed by two. And the kite? I did not get the actual area of the sail but it lives, on the foredeck, in a bag that would be hard to get into the average sailmakers Ford 350 Econovan.

So just where does one start with ‘sailing with young sailors’ at this level? The same way one does it with any other boat, how to get off the dock. At 183 feet and 550 tons more or less Zenji is not simply pushed off the dock by a collective crew heave. It is an example of the kind of teamwork that is the hallmark of good, nay great, teams. On the first day, I took my charge to a convenient watching place, out of the way and discussed the co-ordination, teamwork, communications and calm required to move this ship. The mate, another pleasant young Brit, James, was at the stern with a hand held radio, another crew member was at the bow, with radio speaking to Matt, on the bridge coordinating which line was to be cast off, in what order, the distance off the dock, distance to the pier astern of us and so on. Zenji has bow and stern thrusters, so they supplied the collective heave, to perhaps 15 feet of the dock at which point Matt engaged the (two) engines and we started to idle south. This particular process was duplicated daily over the course of the regatta. All the time we were motoring out to sea, to hoist sails, there was a look out on the bow offering a running commentary on other traffic and lobster pots.

Friday was quite a bust with very little air making spinnaker work exasperating. Here, Sarah, Isabella and Mikaela seem to be managing the stress with aplomb during lunch. Two of my aft deck crew, Owen and Bill, are seen in the background, discussing tactics, one hopes.

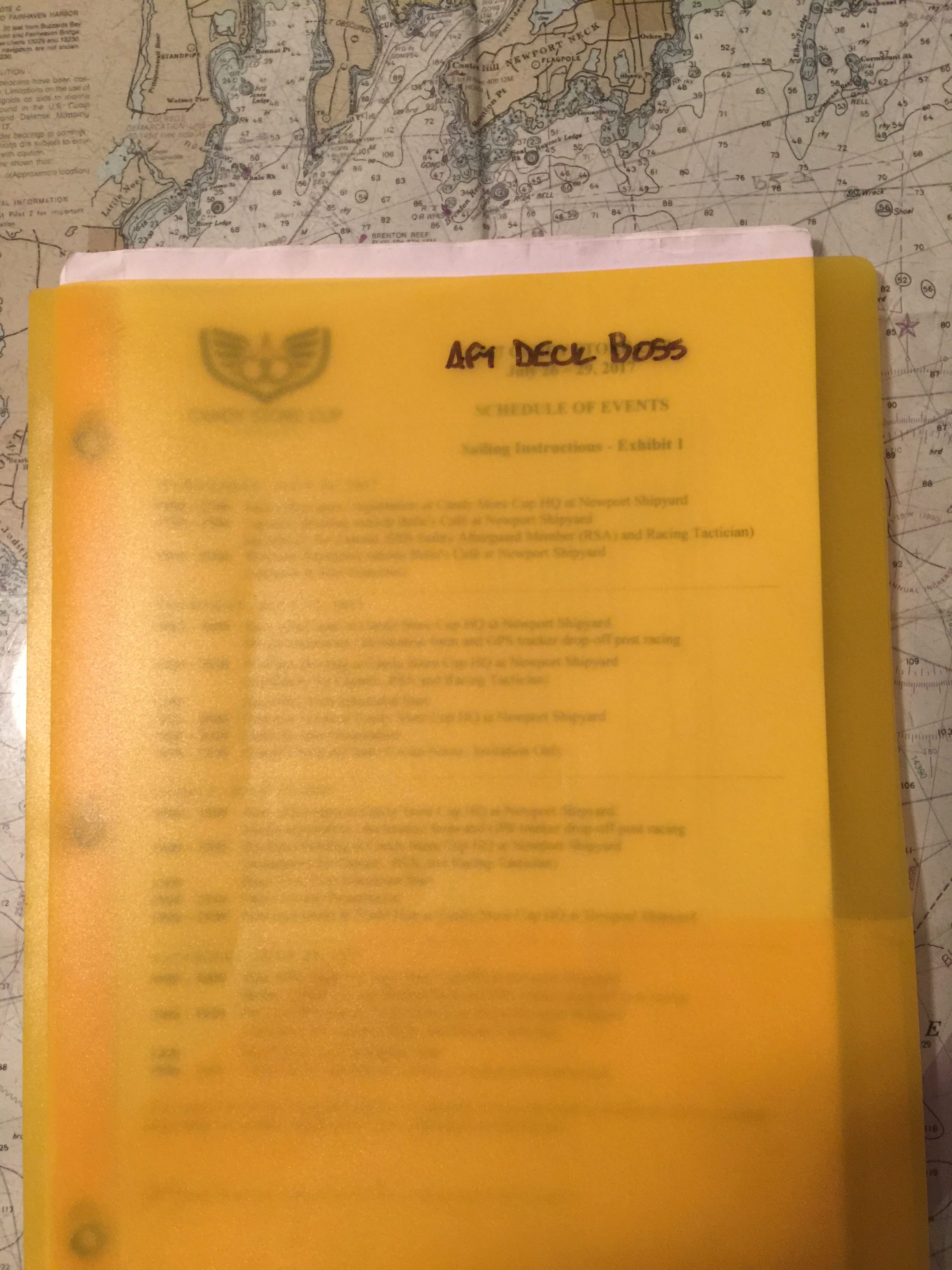

At the first gathering for the race crew, the Monday prior to the regatta, Matt ran through the housekeeping issues, safety, where the day head was, where to stow our kit and so on. He also handed out ‘The playbook’ for the crew, ship and regatta.

The ‘play book’ was an interesting read I shared with Sarah, the Prout sailor on Tuesday, our second practice day. Multiple copies of this ‘book,’ secured in waterproof sleeves and bound in yellow plastic binders held all the information anyone on the crew would need during any evolution to do with sail’s and sail handling. The crew numbered about 20 ‘race crew,’ plus James, the mate and 3,4 deck hands. The binders were labeled, and mine had Aft Deck Boss written across the top.

The discussion with Sarah was on the idea that sailing something like this required multiple people to do even the simplest task, and given the bulk of the race crew had not sailed together and in some cases, like me, not on the boat at all anything that could be done to get every one, literally, on the same page was good, sound and prudent seamanship. A discussion of just what Seamanship is, was a constant theme during the four days with the ladies.

To give one a sense of the size of Zenji, this is a picture of bowman, Juggy, going aloft to check in something. He is between the second and third spreaders.

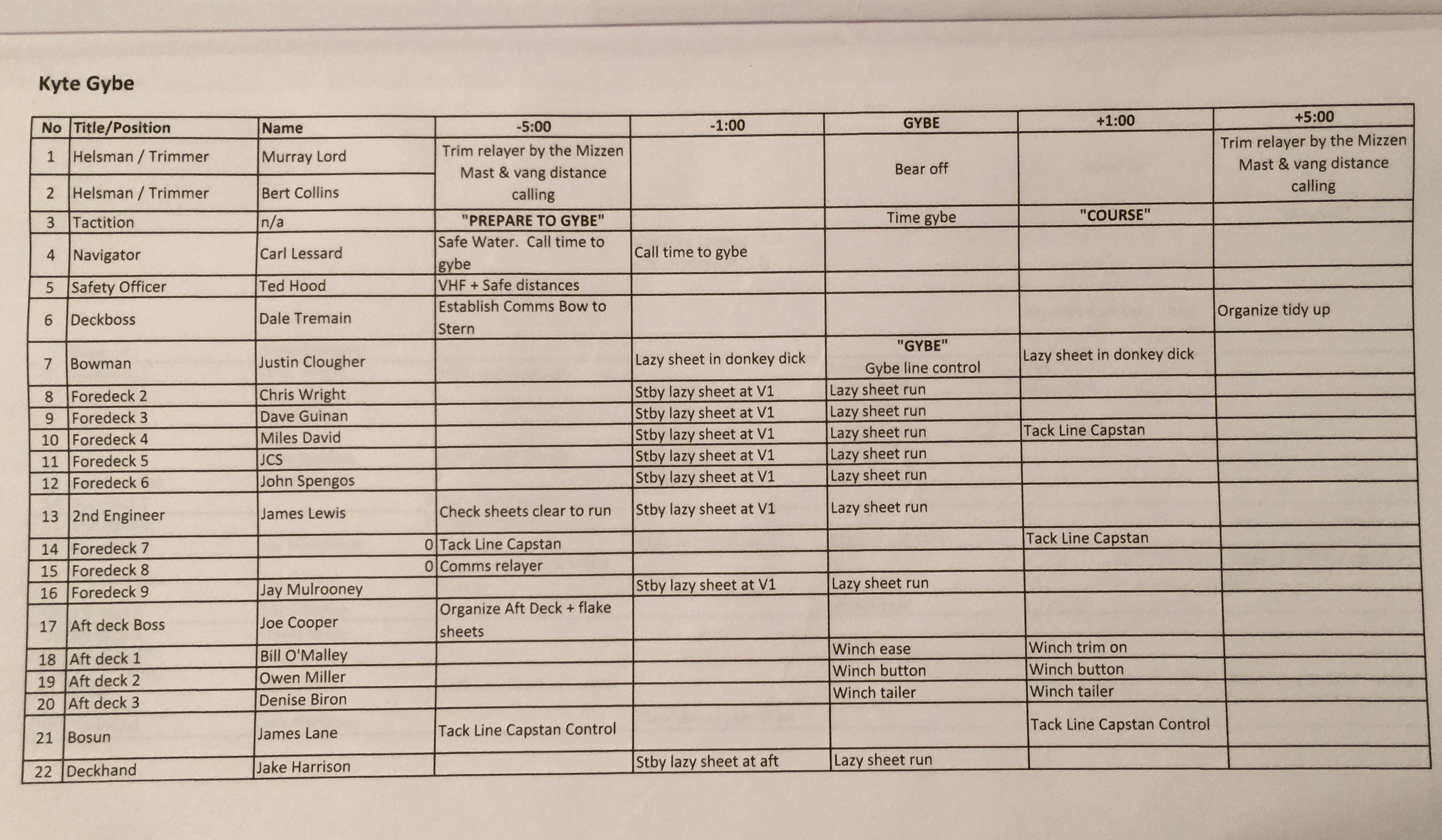

The five main pages in the book were spread sheets of the crew dispositions and tasks for each maneuver. OK, this might not be critical in a 420, a J-70 or a 50-foot handicap offshore yacht. But the idea I discussed with Sarah was that each position on the ship has a role that varies by what evolution is about to happen.

The procedure aboard Zenji, for gybing including the 5 minute warning, then a one minute, then the action: GYBE and the post action activities.

I was honored to have three really skilled sailors as ‘my team’ on the aft deck where the kite trimming was to happen and introduced Sarah to them and we discussed the sequence and timing of setting, gybing and dousing the kite. Outside gybes were, by the way, great entertainment with about 250 feet of sheet moving around the bow in pretty short order…

The two headsail were on furlers, vast monstrosities, hydraulically driven from the bridge, that we wrapped in towels lashed up with light line and covered with multiple passes, mummy like of a 12 inch wide roll of a self-adhesive version of a shrink-wrap like plastic to protect the blinding stainless steel finish and the 30 mm diameter hydraulic cables.

The genoa furler on Zenji is like everything else on the ship, BIG. The light line on the deck is the lashings we had securing the towels, under the instant shrink wrap. The black line is one of the forward dock lines.

During Sarah’s, and on subsequent days, the other ladies, pre-departure tour of the bridge, they were introduced to the control panels for managing the loads on this ship. Everything from the centerboard up & down controls, the sail hydraulics, (the main and mizzen were in-boom furling arrangements) headsails in & out, headsail sheet controls-they were led to under deck captive winches. The crew was admonished to stand out of the way of the genoa sheets, at full crank there is roughly 10 tons of load on the 25 mm spectra sheets, and so on. The headsail sheet warning led to a discussion of ‘standing in the bight’ and a couple of quick tales, that almost all the crew had, of someone getting hurt when standing in the bight and a block let go. All of this hydraulic power was under the command of the Toggle Master, one David Dawes, formerly the master of the Oliver Hazard Perry, the RI tall ship.

My take on all this to the ladies was along the lines of ‘anytime you have a team of any number of souls doing anything, it is important to break the tasks up into bite size and manageable pieces, to have competent managers in each area, to make sure that every team member knows what the goal is and when and how to do their task. This example happened to be on a sailing boat, but such principals are very handy in the non-sailing world’.

Handling the kite is, in essence, the same as any other kite evolution, except it takes longer and requires a lot more coordination. To this end the bowman, Newport local, Justin Juggy Clougher had a radio, as did I, and also Dale Tremain, aka Crusty, the overall Deck Boss, so co-ordination between the bow and stern teams was thus rendered about as straightforward as on any Weekend Warrior 40 footer, may be better.

I had plenty of opportunities to reinforce one of my common memes that the physics of sailing do not change with the size of the boat, merely that the boats get more complicated to handle. The handling of the sail(s) and the required coordination with the helmsman are all the same, regardless of the LOA.

The primary difference in spinnaker handling was in the amount of line (sheet) moving and the speed with which it needed to move particularly during gybes. This speed required that the kite sheets be ready to run and with no kinks in them. The sheets were flaked out on the aft deck, which was fortunately big enough, in long, perhaps 10 feet per pass, all neatly nested next to each other. This action gave me the opportunity to discuss the problems that arise if the sheets fouled on something. The action of preparing for the next evolution is another theme of seamanship I try and constantly bring to the attention of the ladies regardless of what we are sailing on. The ‘what will happen next and what will we do if it goes south’ mind set being a pretty good working definition of seamanship.

Speaking of seamanship, this 30 second video is of Billy Black out doing his thing. The red line, secured to the rail, next to the Zenji crew, is the coiled spinnaker sheet

Five of the ladies had the opportunity to sail with me on this Kaper. They all enjoyed themselves, even if sailing was not strictly what they were doing. The trio on the last day did however get to experience that full effect of sailing on a Super-yacht, the ancient art of Wash-down and Shammy. The ladies took it all seriously, even while smiling and laughing, their signature trademarks as far as Prout sailors are concerned and worked just as hard as though they were a regular part of a big boat crew.

If sailing incorporates the idea of seamanship, even in an Opti, then a day or two on a small ship like Zenji is, while not strictly sailing, an eye opener into the larger (literally) world of sailing and seamanship, where everything needs planning and forethought, two key hallmarks of good and sound seamanship.

After the last race, the work of cleaning up begins. Here Isabella working is on the tidying up the kite sheets, which probably weight more then her.

My last job of the last day was to present Matt with a Prout Sailing shirt as a gesture of our appreciation of his willingness to help give young sailors a look at another card in the vast deck of this activity we do called sailing.