Breaking a mast is by no means outside the realm of possibility on a sailing boat. Even if you have done everything right yourself there are always outside factors, never more so when racing. And frankly it even happens to the US Navy.

During the New York Yacht Club’s Annual Regatta, 10-12 June 2016, the race committee sent the IRC classes offshore from Brenton Point. Among the boats racing were two boats from the United States Naval Academy in Annapolis. These so called Navy 44’s, now about twenty years old were purpose built training boats used by the Academy for, certainly sailing, but team building, offshore sailing experience, resources management and leadership training. All skills these young sailors will be called upon to use for the next twenty years at least. A wise man, a pilot, once said to me any one can fly a plane in a straight line, it is knowing what to do when something goes wrong is the trick.

And so it is with sailing. What do you do when something goes wrong? When it DOES go wrong is not the time to find out. For a successful recovery from any incident there needs to be a plan in place for all hands to follow. Nowhere is this a more needed component of sailing than with the Naval academy midshipman due to the generally low level of sailing background and experience the Academy students have compared to the passages they make and the responsibilities they take on.

I was racing on the same course as the Navy boats and when the Race Committee abandoned racing for the day, after the wind piped up over 30 knots true, we all made our way in. On our boat we heard some traffic on the VHF about a boat with a broken rig but were occupied with keeping our own house in order and so did not really think about the dismasted boat for a few minutes.

As we motor-sailed towards Castle Hill it became clear the dismasted boat was one of the Academy 44’s. The first thing that struck me was that the mast was on board. This is generally a rare situation, masts go overboard most often to leeward and so are usually cut away and lost to the sea. Hummm, I wondered, what happened here? What was different about this dismasting that allowed the Midshipman to get the spar on board……?

This post is the result of an interview with the Commanding Officer of the 44, Midshipman James Reynolds, (entering his senior year at the Academy) a couple of days after the incident.

The wreckage of the broken mast lashed down on top of Defiance. Carina’s bow went up across the side deck & smashed the hand rail.

I was particularly interested in the dynamics of the crew for several reasons. One is the Navy sailing squad is commonly populated by students with not much, if any, sailing background. In this case Midshipman Reynolds had the most sailing background growing up sailing Opti’s, 420’ and, living in New Jersey, scows on Barnegat Bay. Of the 9 Midshipman aboard, including two women, one of whom was the executive officer on the boat, about half had some time on the boats and at sea. So by and large an inexperienced crew, arguably less experienced in absolute terms than perhaps any crew in the regatta.

Then there was the fact that the mast was on deck, an unusual aspect to a dismasting. On the other hand we are talking about some of the brightest and capable young men and women in the country who are being trained and groomed for major leadership roles in the United States Navy and so broadly speaking on behalf of the US in general.

The Mid’s did well to secure the spar. That was just about the third order of business after a head count and inspection below to make sure the hull was not holed. You can see the dent in the toe rail as well as some of the scratches. Probably due to the angle of heel AND the classically raked bow, Carina did not penetrate the hull.

Midshipman Baldwin outlined the process where by non-sailing freshman are introduced to sailing starting with a few hours of classroom instruction. They then move to hands-on sailing in the Academy’s fleet of Navy (Colgate)26’s. From this sailing the ‘big boat’ teams are selected based on criteria including aptitude and initiative.

A review of the Academy’s sailing website demonstrates the details in which the Midshipman are instructed and the goals including-The following paragraph is a Cut and paste from the site:

Offshore sailing serves as an ideal platform for team building, small unit leadership, and seamanship skill development. All planning and decision making involved with day sailing and long distance transits and racing is made by midshipmen team members. Skills developed include navigation, strategic planning, resource management, vessel maintenance, weather tactics, and racing strategy.

A broken mast is one of The Eight Events* for which crews on sailing boats in the ocean (even only a few miles offshore of Brenton Point) must be familiar.

So, on with the story:

On the way out to the start the breeze was in the 18 to 20 knots true from the north-west. Baldwin told me that there was a pretty standard team meeting that covered the action for the day, what to expect, especially with the breeze at hand and the forecast for stronger winds later in the day and the admonition to be aware of the loads, do not stand in the bight of a line, double check what you are doing and to be steady and careful.

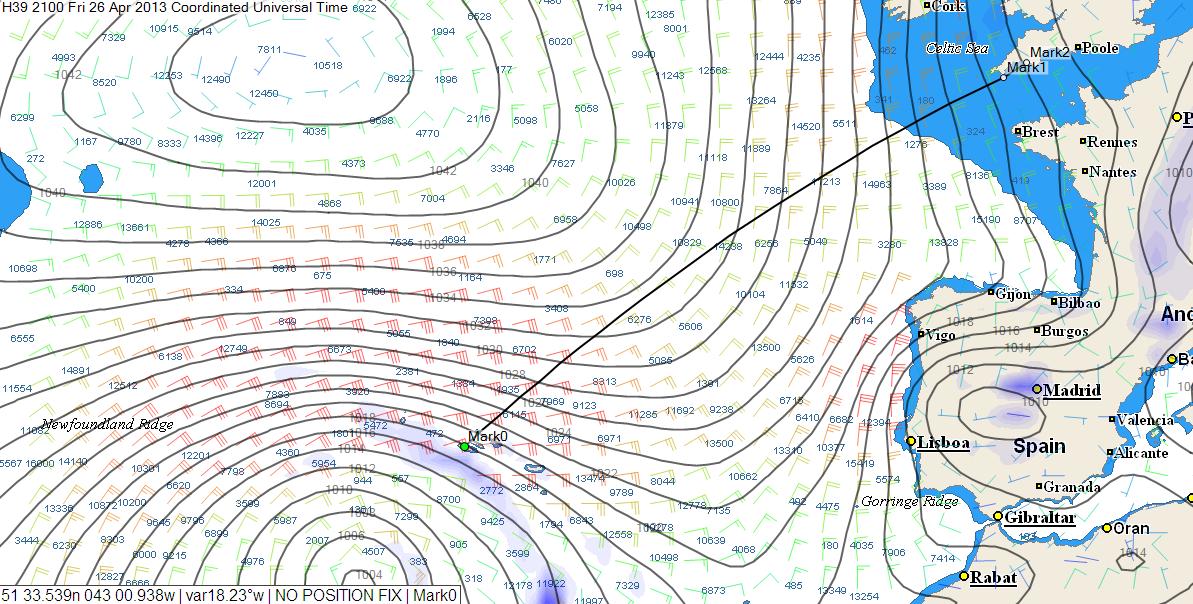

The incident occurred on the second upwind leg of the first race. Defiance, the Navy boat was sailing up wind on starboard tack in about 20-22 knots of true knots wind with a full main and number three set.

Mid. Reynolds, acting as tactician and so not steering, saw Carina, the venerable McCurdy and Rhodes 48 footer sailing upwind towards them on port tack and determined a crossing situation was in the offing. He made the ‘starboard’ call and Carina responded by easing sail’s and steering to pass astern of the Navy boat. Baldwin is not one hundred percent certain exactly what caused the next event, but thinks that Carina was knocked hard by an errant wave (there was a nasty chop left over from Saturday) that hit Carina hard and pushed her up to where she collided with Defiance.

Defiance being on Starboard tack was rail down to Carina and so the latter, with her classically raked stem, slid up the deck of Defiance, damaging the toe rail, smashing the hand rail pushing a winch of its mounts, hitting and breaking the boom close to the gooseneck and ripping the lee side chain plates out of the boat. The force of the collision pushed the Navy boat up into the wind, with the result that the mast fell more or less directly aft, landing on the aft rail. This answered the ‘how did they get the mast aboard’ question, since it never actually went overboard.

It broke in two places, right at the partners and about 12 feet up the mast. The crew was of course hiking out on the weather rail and scrambled to avoid being hit. The after most crew member actually jumped over board so as to avoid the spar crashing down around him. He had the presence of mind to hang on to the lifelines as he did so and so ended up hanging onto the boat and he was promptly gathered back aboard.

I asked what happened in the first few second after the mast fell. First action was a head count. Reynolds ended up in the cockpit, on the floor and could account for half the crew in his vicinity. The XO was further forward and reported all hands aboard and un-hurt, although in a few minutes one of the crew was taken below with what transpired to be concussion. Next step was to dispatch a hand down below to make sure the boat was not taking on water. Parallel to these activities, all in the first few second, the ships Safety Officer, Jon Wright took command of the boat. Not surprisingly, working for the Navy Offshore program Wright has vast experience across all manner of boats. What happened within the next thirty seconds?

The crew emerged from under the sails. The bowman and foredeck hands started to work on getting the sails secured. The top 20 feet or so of mast was lying across the stern rail and dipping in and out of the sea, aggravating the situation with the mast flailing around on deck. They were able to get the headsail secured but had to cut the mainsail at the first reef, luff to leech after which they could remove the mainsail from the mast. Next task was to work on securing the mast. The boat was now sideways to the sea and was rolling heavily and so aggravating the situation with the mast in and out of the sea.

I asked if the actions were all on initiative or on instruction from Wright, (known almost universally as JW)? A combination of both was the answer. The crew had had sufficient instruction and, while not actually handling broken masts, training in what to do. The lee rigging, now disconnected from the boat was fortunately lying in the water, minimizing further potential damage to crew and boat from flailing wires.

One of the crew radioed the Race Committee advising them of the incident. The RC responded by sending the Windward mark boat to assist.

One of the crew remarked on having been hit, feeling lightheaded and unwell. She was dispatched below under the care of the XO, the other young lady in the crew. Once ashore she was diagnosed with concussion.

Within five-ten minutes the spar was secured along the centerline of the boat. The remains of the boom had been freed but discarded. The wheel had been damaged when the rig hit it and was out of commission so the emergency tiller was rigged.

In a brief conversation with Rives Potts the owner skipper of Carina, I asked him if he had the opportunity to make any observations of the navy crew’s response. Potts told me that Carina immediately lowered sails and stood by. Once they ensured their people were OK and the boat sound, Potts had the opportunity to follow the action on Defiant. He remarked on the calm and professional way the young Navy sailors conducted themselves. ‘There was no yelling or shouting, they looked very cool and collected, and went about securing the boat although they scuttled the boom. It seemed like they had the mast secured very quickly. All in all a very impressive piece of work by young sailors’ he told me.

In a separate conversation with Jon Wright, again a pretty quick one-he and Potts are, as I write, preparing to go to Bermuda and the forecast is for hard winds-He concurred with Potts in the calmness with which these young sailors conducted them selves. He confirmed Reynolds remarks that the first order of business was to make sure every one was on board and not injured. Closely followed by an inspection down below for hull security. He agreed with Potts with the view that the actions and demeanor of the crew were very calm and professional. The crew worked together, with different members proposing solutions to the micro problem in their particular area.

The take away from this discussion and incident?

Planning, preparation and a game plan.

At one of your off season crew gatherings, walk the troops through the eight events, noted below, and work up an Actions Plan for each one. The Navy sailors were fortunate to have this accident in broad daylight, 4 miles offshore and moderate sea. These circumstances may not be in place if your rig comes down.

*Coopers Eight events:

In the Junior Safety at Sea seminars produced by the Storm Trysail Foundation, I cite the following events as situations for which there needs to be established plans and protocols.

Dismasting, holing, man overboard, medical emergency, abandon ship, fire, rudder or steering failure. (They sound the same but are a bit different in the required response.)

During the Storm Trysail Foundations junior SAS every year, local high school sailors are introduced to the issues surrounding operating a big boat in a safe and seamanlike manner. Here, Sheila McCurdy, the hugely experienced former Commodore of the Cruising Club of America and multi-time Bermuda Race participant discusses some of the safety equipment used on big boats.