The Square Head Mainsail–on to advantage side of the equation:

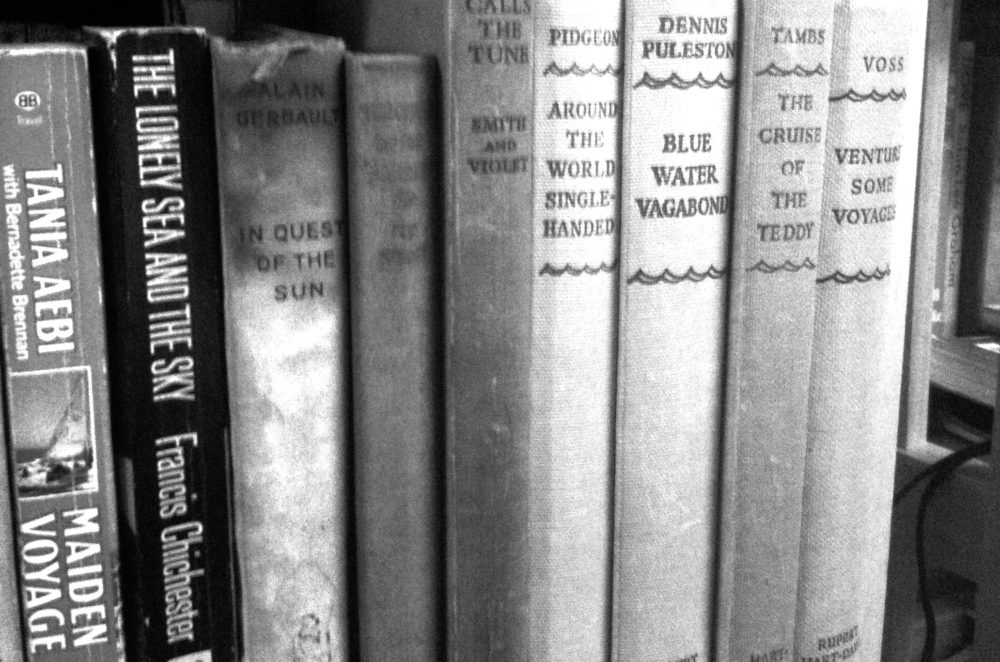

The Square Head mainsail is the default style for the Class 40 short handed offshore race boats. Don Miller Photography image

The previous few essays have focused on the limiting issues surrounding full length battens including, for the vast majority of the normal boats that most of us sail, the backstay.

Briefly I have proposed that:

- There is not really solid empirical evidence that one sail with FLB is faster than the SAME sail with leech battens on the same class of boat and assuming that both boats are prepared to be as identical as possible.

- The Cost of FLB may outweigh the Value a lot of the time

- I will get to the “sail handling” aspect of FLB further along in the series. This area is in fact one of the areas that does offer increased value for the owner via ease of handling the sail: Hoisting lowering reefing.

For now I am going to concentrate on the most obvious advantage and a much lesser known aspect of full battens in general and the Square Top mainsail in particular.

In my experience virtually all discussions with sailors regarding sail shape is one sided, in that it revolves around the sail’s shape and so the implied concept is aerodynamic lift. I cannot immediately recall any discussion where the other side of the lift equation is even mentioned let alone discussed: DRAG.

Drag is everywhere on a sail boat:

Someone with more time on their hands than me could calculate the amount of drag on this boat

The actual hull topsides

Cabin profile

Rigging

The sail’s surface

The width of the roller furler or furled headsail when sailing with a staysail

The furling drum

The anchor

Rails, life lines stanchions

The dinghy stowed on the bow or in Davits

Cruising boats carry lots of kit and it is all drag.

Halyards

Dodger

Life raft on the cabin top

Bimini

People standing up- This is why most good race boats have the guys all sitting together in breeze or laying low in light air.

Radar either tower astern or on mast

Radar reflectors…..You get the picture.

What is missing from this list?

It is one of the reasons why the square head sail has emerged over the past few years.

We have discussed the usual limiting factor for the size of the roach on most boats is the backstay, closely followed by adherence to a handicap racing rule.

Enter the “open” class boats, in particular the solo offshore race boats. This cohort encompasses the Mini 650 class, the older open 40’s and the much more successful, as a class, Class 40’s, the open 50 and 60 foot mono-hulls and their multi-hulled cousins and in some parts of the world open class skiffs like the Aussie 18 footers.

None of these classes (I am not 100% certain about the 18’s) have any restrictions of sail size or shape, only number and type depending on the individual class and the race.

If Bigger (more area) is Better, so the square top sail is born.

The one element missing in this discussion so far is the mast.

The mast, the square top sail and full length battens are all interconnected.

The Twitter version:

The mast is drag

The square top sail minimizes that drag

The ST cannot work without full length battens

ESPECIALLY in this case, the FLB need a low friction track because of the great compression generated by the ST sail.

The NPR version:

Because it is sticking up in the air, the mast is 100% drag, at least for the purposes of this essay-Ignore the wing masts and wing sails please.

Over the span (the fore and aft width of the sail-the girth.) the drag from the mast is reduced because the air is smoothed out by flowing across the sail.

As the sail ascends into the air on 99% of boats it gets narrower, again almost universally due to tradition as manifest in the backstay.

This image gives a good visual of the issue at hand-Namely the top 3-4 feet of mainsail-on a 40 footer-is not contributing to reducing the drag from the mast.

At a point that varies for all sorts of reasons this reduction in drag is reduced. The drag from the mast starts to increase.

The point is that usually within a few feet of the top of the spar and for a rule of thumb it can be where the girth of the sail is less than about 4 or 5 times the local for and aft length of the mast, the amount of drag over comes the amount of lift generated by the sail.

For instance, let’s say the mast is 6 inches fore and aft. 4 or 5 times 6 inches is 24-30 inches. So in this example the drag starts to increase, dramatically, at that point on the sail where the girth is less than 24-30 inches wide fore and aft because there is not enough girth in the sail to smooth out the turbulence created by the wind hitting the mast.

This beam on image shows the ratio of the mast’s fore and aft length to the width (girth) of the sail. This is obviously a conventional mainsail and was built to comply with local racing handicaps. As on almost all conventional yachts, as the sail approaches the mast head the position of the girth on the sail diminishes. On this Sabre’s main the girth equal to 4-5 times the masts span is a little lower than half the distance between the mainsail head and the top batten. Functionally then the (mast) drag starts to increase dramatically somewhere above the top batten is. I enlarged the image and used a metric rule against the screen to determine this.

Enter the Square Head sail. This sail profile minimizes the drag from the spar as well as being much more sail area.

I do not have many close up images of the relationship between the mast width and the sail girth as for the one of the Sabre above this image, but I think you get the idea. This image courtesy of Don Miller.

BUT

It is functionally impractical for any boat with a backstay. Unless of course you want to lower the mainsail every time you tack which may sound like a pain but again find out what the customer is trying to do with his boat sail goals plans etc. I did do two offshore cruising boat sails that were exactly that big roach that would not clear the standing backstay. In one case, the image below, it was a bit difficult to get through in light air although he reefed in about 14 knots of wind, so the roach was easier to deal with the first reef in. I did another offshore cruising mainsail where the owner specified that he would sail with the first reef in if lots of tacking was going to be involved. The roach in this sail was even more aggressive than the first one.

This is the roach profile of the first boat I mentioned in the paragraph above. Many thanks to the owner for providing the image. www.mccubbin.ca/boat

This particular boat that I did the working sails for was built with two configurations-One with this large roach and NO backstay at all for coastal cruising in and around New England. The two light lines you see on the sail are more conventional runners for headstay tension, but are not really required to keep the rig in the boat. The spar was of course so designed. And a smaller main WITH backstay for going in the ocean. This is one way to do it. Boat was a custom Bruce King design.

For boats with such sails, very large roach OR square head, enter the twin topmast running backstays, generally referred to as “the runners”.

As the name implies, they are running backstays that attach to the masthead and are adjusted by a two or three part purchase led to a winch.

This image gives a bit of an idea on the twin running backstays idea. Yes, this is a race boat, a single handed forty footer from the 2009 O.S.T.A.R. The two padeyes with blocks on the transom are part of the three part purchase this boat has. The blue cordage crossing forward of the starboard stern rail is the last fall prior going to the winch through a clutch at the very edge of the image. The pair of blocks adjacent to the base of radar plinth are for the mainsheet.

Upon contemplation it will be seen that this is not something to be undertaken lightly. Many things need to be contemplated, not the least of which, in no particular order are:

Boat & Deck hardware lay out

Mast strength

Standing rigging configuration

The degree of sweep of the spreaders

The skill of the operators and

Their willingness to put up with this added task when tacking

All these factors contribute to the reason why most “cruising” boats do not have square head sails.

Next up running backstays, batten compression and hardware for the battens.

This is my mini-650 on her first sail late in the afternoon in August 1995. Scott Bradford assisting and checking the spar. This was the first 5 minutes of sailing after her launch. At the time this roach profile was considered to be huge. If you look at the luff you will see the luff sliders I used-NOT ball-bearing at all, but the best available option on the day. I was more interested in keeping the sail on the boat during handling.